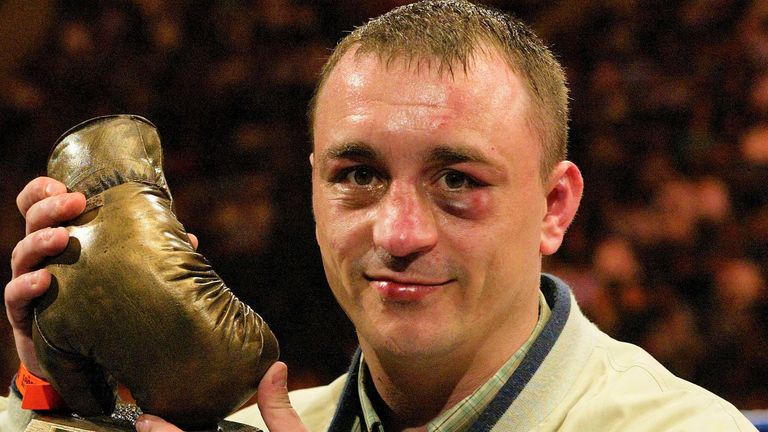

Peter Buckley interview: He lost 256 of 300 fights but ‘the King of the Journeymen’ occupies a spot in history

On one occasion Peter Buckley was halfway through his dinner when he accepted a fight in a couple of hours’ time; once, he had broken down at the side of the road but still managed to answer a desperate plea seeking a willing opponent.

In 300 fights he lost 256 and won 32 – this is the bizarre life of ‘The Professor’, so-called because of a respected ability to teach talented prospects about the cruel realities of the boxing ring. Buckley would lose, collect his pay-cheque, wave the winner off onto a brighter future then resume his role as the perennial runner-up whenever the phone next rang.

But this is a great success story. Buckley was in jail aged 15 when his father died and boxing offered him a route away from his troubled teenage years. He now occupies perhaps the strangest place in British boxing history, widely regarded as the best-known of the ‘journeymen’ who provide the invaluable service of being a willing punchbag for future champions, used as a measuring stick for kids with ambition and a reality check for those who will never make it.

The key trait is availability. Buckley never turned down the offer of work, even as the defeats racked up. Often his willingness was taken to farcical extremes.

“I’d be sat at home and [my manager Nobby Nobbs] would ring to say: ‘There is a fight going’,” Buckley told Sky Sports.

“I’d ask when.

“He’d say: ‘I’m on my way to pick you up’.

“Once I was having my dinner after training. Nobby phoned and said: ‘There might be a fight’.

“I asked when.

“‘In two hours’.

“I carried on with my dinner when he phoned back and said: ‘The fight is on’.

“I was once under my car, it had broken down, I’d burned my arm. Nobby phoned to ask if I could get to Nottingham for 6pm. It was 4pm and my car was broken down.”

Somehow Buckley arranged transport, arriving in the ring promptly. Of course, he lost, but there is wider context to his role.

“I bought a new car the next day,” he smiled.

It is a tumultuous life. He once took a four-hour train to Scotland without phone signal for a fight.

“I got off the train, looked at my phone: ‘Sorry, the show is cancelled’.

“One night I got home at 5am and got a call at 11am saying there was a show. I turned up and one of the doormen from the night before was there!

“I was hungover but it was only [six rounds of two minutes] so it was okay!”

Buckley’s intention was never to become a laughing stock, a travelling loser from ring to ring. But boxing has a nasty way of beating the ambition out of some people.

He was a good amateur, winning 50 of 54 fights, when he was alerted to the possibility of using his talent to earn some money. During a drinking session at his local pub he agreed to go pro.

“I thought: ‘I’ll have a few fights and just see’,” he said.

“After 100 fights I thought: ‘I’m getting used to this!'”

The Birmingham super-bantamweight drew on his debut then won six of his next seven fights.

“I wasn’t a journeyman. I was doing OK.

“When I boxed Duke McKenzie [in his 24th fight] I realised about levels. I thought I’d beat him, that’s how naive I was.”

McKenzie went on to become a three-weight world champion and one of Britain’s finest boxers. Buckley was merely a footnote in his story.

“I got a rude awakening that night,” he remembered. “I took that fight at a day’s notice. I was never going be at that level but I knew I could handle British, European level.”

It was a fight that spawned two historic careers – as McKenzie progressed, Buckley regressed into the role he is now feted for.

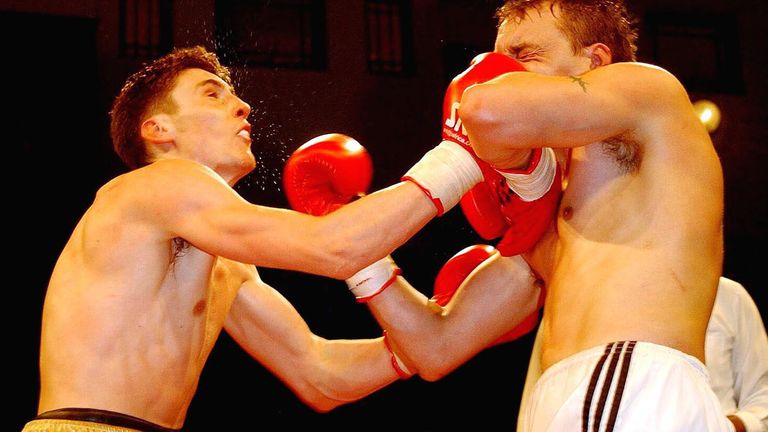

Buckley carved out a niche for test-driving the bright young hopes of British boxing. He would not fall over quickly enough to be labelled a waste of time, but nor would he threaten to win. He was a tough night’s work for inexperienced talents who were still dipping their toes into the water.

He fought ‘Prince’ Naseem Hamed, Kell Brook and Lee Selby among many others.

Barry Jones would also go on to become a world champion but told Sky Sports about the value of fighting Buckley: “Someone pulled out and Peter got the call. I didn’t know how good or bad he was but I found out quickly.

“He was riding every shot which was frustrating. Peter always knew where you were.

“He wouldn’t fire back often but he took the sting away. You couldn’t hit him clean, you couldn’t reach the target. Very rarely would you hit him.”

Buckley explained: “The better the fighter, the better I fought.

“Because when you fight a novice you don’t know where their punches are coming from, because they don’t know themselves! When you fight a top-class kid they will be textbook which is easier to read than a novice who hits you with silly shots.”

A defensive shell that became Buckley’s trademark was honed in a typically unorthodox way.

“I injured my shoulder and, instead of having six months off, I had one month off,” he said.

“I’d warm up in the changing rooms and my shoulder would pop. I learned to defend with one arm.”

Buckley would receive a call most weekends with promoters valuing his small contribution to the eventual success of an up-and-coming talent.

“My ideal night was coming out without a mark on me,” he said. “I just wanted to move around.

“I wasn’t out to win titles.

“[Buckley’s manager Nobby Nobbs] said: ‘You have to earn as much money as you can without getting hurt’.

“To him, if you came out with black eyes, he wasn’t doing his job.”

Such an unusual career that is defined by its failure has thrown up a mixture of memories.

“The worst? I boxed Bradley Price for the second time,” Buckley said. “He was a lot bigger than me.

“His first punch was a jab that dropped me on my pants. Right hand, left hook, down again. The referee called it off.

“My highlights? I won two Midlands titles at different weights. And I fought for a WBA intercontinental title in Austria against Harald Geier. I was treated like a superstar over there – national anthems, everything!

“It was my first 12-rounder, I’d never had so much time in my life [to prepare].

“I put him down in the ninth round but the referee practically wiped his boots for him!

“There was nothing in it. He then fought for the world title and got knocked out in 17 seconds.

“If I fought the same Mexican geezer for a world title he wouldn’t have knocked me out in 17 seconds.”

There is often a sadness at the heart of these journeymen boxing stories.

Kristian Laight, who retired when he matched Buckley’s 300-fight record but lost even more (279) told Sky Sports in 2018: “Of course I’m a failure in terms of boxing. But when my little boy is older, people will ask him if he was fed, and had clothes on his back. He does. I went out and did it the hardest way imaginable to earn for my family.”

Buckley, it is worth remembering, did not aspire to a career full of losses. He just readily accepted the cards that were dealt to him. He navigated through boxing’s inner-workings and found a benefit to himself.

He was stopped just 10 times in 300 fights, a remarkable demonstration of his durability, but he passionately insists that five of those were misjudgements from the referees.

There is a ruefulness when Buckley explains losing 256 times.

“Take 100 of those fights – some of those were by half a point,” he insisted. “I’ve got 12 draws – they were 12 wins, really, because I was away from home.

“I could try my heart out and still get beaten. Or make it as easy as I want and still get beaten. For the same money.”

He concedes there are regrets: “I took fights at late notice when I’d been out the night before. I liked going out.”

His influence has, indirectly, reached the world stage. He named Duke McKenzie as the best opponent he ever fought (“Naz was a great fighter but when I fought him? He was on the way up”).

Kell Brook was derided by Errol Spence Jr at the press conference for their world welterweight title fight for debuting against someone with 189 losses – that was, of course, Buckley.

He even once fought on a Mike Tyson undercard.

Buckley retired in 2008 with a rare victory, ending an 88-fight winless run. His autobiography King of the Journeymen: The Peter Buckley Story is coming soon and depicts an abnormal existence that teeters on the fine line between notable success and abject failure.

Source: Read Full Article