Luiz Felipe Scolari interview: ‘If Brazil could play Germany again, I wouldn’t change a thing’

Scolari could only watch on as Brazil collapsed in Belo Horizonte

“Germany played a perfect game and we made mistakes one can’t make in a semi-final,” Scolari said in new book, How to Win the World Cup: Secrets and Insights from International Football’s Top Managers.

“If I had chance to play the match again, I wouldn’t change anything in terms of what we studied and the tactics we worked . We all know that game was one in 100 – one in 1,000 maybe – something absurd that happened, so even if I could go back and change the team with information we had gathered from Germany, we’d do the same again.”

Recommended

It’s a startling admission from a manager who was in charge of the greatest humiliation in Brazilian football history since the Maracanazo – the Agony of the Maracana – when the Selecao lost the de facto 1950 World Cup final against Uruguay in front on their own fans.

Scolari admits his side were “stunned and scared” by Germany’s potency as they went 5-0 up within half an hour – scoring four goals in six blistering minutes – but says this was as much to do with Die Mannschaft’s brilliance as Brazil crumbling under unbearable pressure.

Scolari consoles Brazil’s Oscar after the 7-1 thrashing

Several years on and the 73-year-old’s faith in his coaching team – which included another former World Cup-winning manager in 1994 champion Carlos Alberto Parreira – remains unwavering. And it’s testament to the meticulous preparation that went into the match that Scolari wouldn’t alter his approach.

Yet looking back on the Brazil’s home tournament as a whole, there is something that Scolari would change about 2014: the expectation.

“For a Brazilian, the World Cup represents the biggest universal tournament a player or a manager could imagine. There is only one objective: to be champions – the Brazilian people don’t accept second place,” Scolari explained.

“The demand and pressure to win the World Cup in Brazil [in 2014] was intense and very different to the one in 2002. In 2002, we were a team that had a chance, but in 2014, Brazil were obliged to win the World Cup. So that pressure hanging over the manager and players can interfere with the quality [of our performance].

“We had to minimise certain situations for our players and provide daily psychological support, so they would feel less pressure than normal. Because today everyone knows everything through the media, we needed to minimise certain situations, to protect the layers as best we could. But you can’t do that entirely.”

Scolari was no stranger to the pressures of managing Brazil as he went into the 2014 World Cup, though. When he first took the reins on the national team in 2001, the Selecao were facing a more unthinkable situation than a heavy semi-final defeat – they might not have qualified at all.

With only five matches left of the 18-game mini league that decides South America’s World Cup qualifiers, Brazil were clinging on to a top-four spot by virtue of goal difference. Tricky away trips to Bolivia and runaway leaders Argentina remained for Scolari as he was drafted in to perform a rescue act.

But while those struggles to simply book a ticket to the tournament in South Korea and Japan weighed heavily on the group, successfully emerging from the adversity played a crucial role in creating the winning spirit that carried them all the way to lifting the trophy less than a year later.

“Every game we played we had to add points to make sure we could go through, winning or losing we were always in trouble,” Scolari recalls in How to Win the World Cup.

“But with that, we started to create a group. I started to trust the most experienced players, started friendships – not just as a manager – and so we formed a group between us where I had to take some decisions that helped the group to become stronger. So they trusted me a lot and I trusted them, there was reciprocal care, friendship and work, and that’s how we formed an environment almost like a family.”

The ’Scolari family’, as it became known in Brazil, was a cornerstone of the successful camp at the final – that closeness helping in the biggest moments, including coming from behind to beat England in the quarter-finals.

The close-knit atmosphere was also evident on the night before the final against Germany. Scolari remembers feeling the nerves of the occasion himself and it became just as much about handling his own emotion as that of the players.

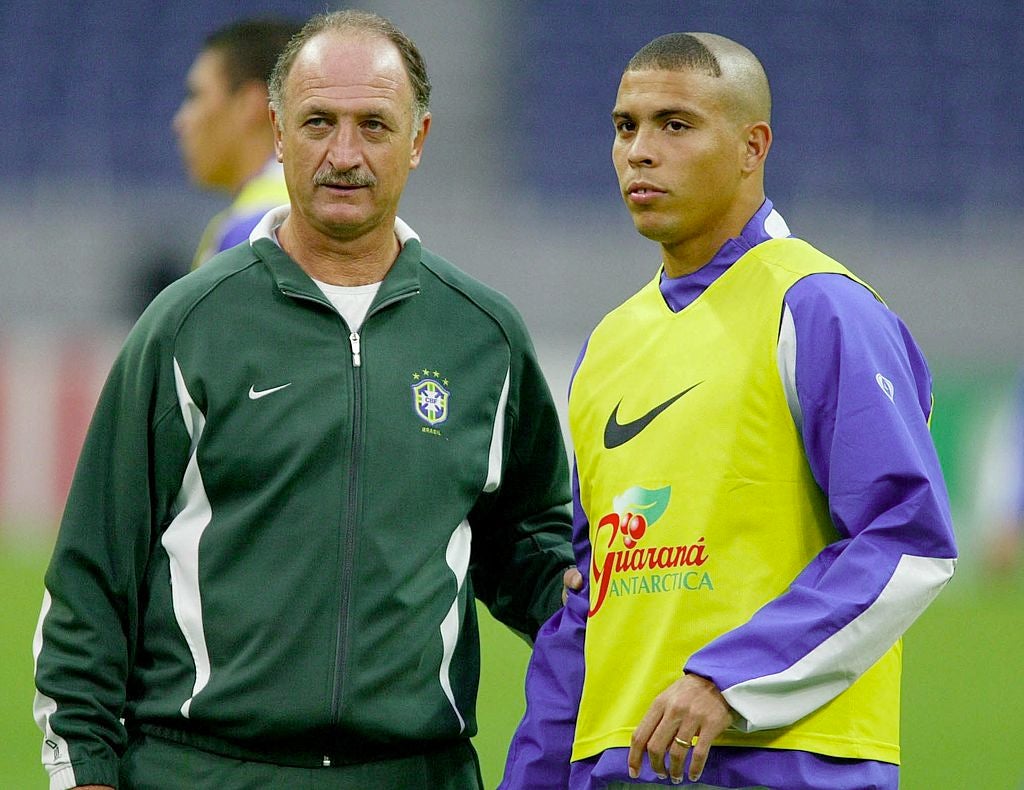

Although with memories of star striker Ronaldo’s health scare that disrupted Brazil’s preparations for the World Cup final in 1998, Scolari’s ability to judge the mood was even more crucial.

“The special work we had to do [with Ronaldo] was to not talk about the episode of ‘98,” Scolari recalls. “We gave no focus to that, we didn’t talk about it so that situation wouldn’t be reignited in Ronaldo’s memories, so it was forgotten by us and him during that moment in the World Cup.”

Instead, it was about holding his nerve. “[I was a bit] fearful, anxious, scared, but trusting in our team,” he adds. “The night before the final, we saw the players were calm, tranquil and that would be put into practice the next day.

“We could see in the players’ faces they were happy with what they had achieved and that they wanted to play a very good match the next day, so seeing that made me calmer that night.

Recommended

“Before that, you get really anxious, you worry about the opposite team, all the details you need to pay attention to, not to make mistakes. That’s normal and after that, when the game starts, everything goes away and you feel normal.”

How to Win the World Cup: Secrets and Insights from International Football’s Top Managers (Bloomsbury) by Chris Evans is out now and includes exclusive interviews with the likes of Sir Geoff Hurst, Roberto Martinez and Jamie Carragher.

Register for free to continue reading

Registration is a free and easy way to support our truly independent journalism

By registering, you will also enjoy limited access to Premium articles, exclusive newsletters, commenting, and virtual events with our leading journalists

{{#verifyErrors}} {{message}} {{/verifyErrors}} {{^verifyErrors}} {{message}} {{/verifyErrors}}

By clicking ‘Create my account’ you confirm that your data has been entered correctly and you have read and agree to our Terms of use, Cookie policy and Privacy notice.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy policy and Terms of service apply.

Already have an account? sign in

By clicking ‘Register’ you confirm that your data has been entered correctly and you have read and agree to our Terms of use, Cookie policy and Privacy notice.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy policy and Terms of service apply.

Register for free to continue reading

Registration is a free and easy way to support our truly independent journalism

By registering, you will also enjoy limited access to Premium articles, exclusive newsletters, commenting, and virtual events with our leading journalists

{{#verifyErrors}} {{message}} {{/verifyErrors}} {{^verifyErrors}} {{message}} {{/verifyErrors}}

By clicking ‘Create my account’ you confirm that your data has been entered correctly and you have read and agree to our Terms of use, Cookie policy and Privacy notice.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy policy and Terms of service apply.

Already have an account? sign in

By clicking ‘Register’ you confirm that your data has been entered correctly and you have read and agree to our Terms of use, Cookie policy and Privacy notice.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy policy and Terms of service apply.

Source: Read Full Article