Iestyn Harris: 1998 Man of Steel on crossing codes and the divide between Leeds Rhinos and Bradford Bulls

Iestyn Harris knows from personal experience how important transparency between all parties is when it comes to his work as an agent.

The 44-year-old has seen professional sport from various sides: as a player in both rugby league and union; as a coach and also as a media pundit prior to moving into his current role which includes him looking after the interests of several current Super League players.

His playing days saw Harris scale the heights in the 13-man code with Leeds Rhinos and Bradford Bulls, with those sandwiching three years in rugby union during which time he won 25 caps for the Welsh national team.

The half-back’s decision to return to league with Leeds’ bitter rivals Bradford in 2004 as opposed to his former club dissolved into acrimonious legal wrangling though, which eventually resulted in the Bulls settling for six-figure transfer fee, and Harris told the Golden Point Podcast how he would handle that if one of his players faced a similar situation.

“You’re in unique positions where you get information from both sides and there is a tendency to want to keep some information away from one side or the other,” Harris told Sky Sports.

“You can end up frustrating clubs and different organisations because they feel they’re all being played off against one another.

“I can see court cases and legal situations coming, and I’ve advised my players several times if they do certain things there could be repercussions.

“I try to make sure that’s not going to develop as my situation did because there was a lack of transparency when I came back… and that really developed into a difficult situation.”

Harris had been a star for the Rhinos during his first spell in league, having made his professional debut at Warrington Wolves aged 17 and made the switch to Headingley for a record £350,000 fee in 1997.

Leeds’ Australian coach Graham Murray proved a huge influence on the youngster too, making the 21-year-old captain and shifting him from the halves to full-back – giving Harris a different perspective on playing the game which would serve him well for the rest of his career.

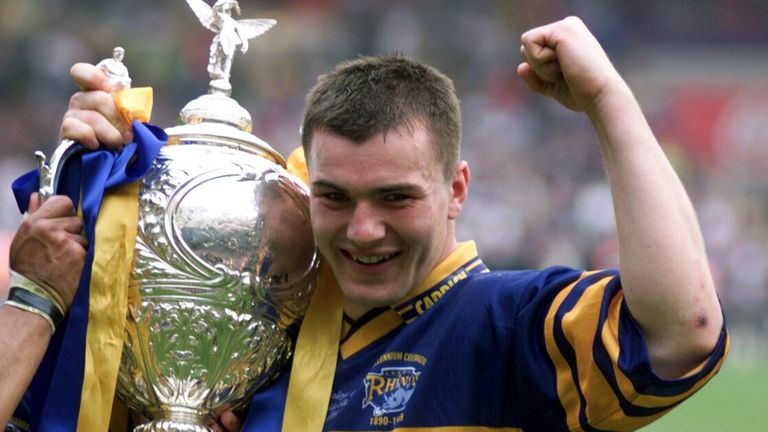

After being named Man of Steel in 1998 as Leeds finished runners-up to Wigan Warriors in the first Super League Grand Final, he led the Yorkshire club to a first Challenge Cup triumph in over two decades the following year with a 52-16 win over London Broncos at Wembley.

To win that first silverware in 1999 was pretty special because it was 21 years since they’d won the Cup. You just felt the pressure removed from the club.

Iestyn Harris on Leeds’ 1999 Challenge Cup triumph

That was arguably the first step towards the Rhinos’ golden era in the first decades of the 21st Century and Harris is in no doubt the signs were there something special was building thanks to the work done to turn the club around behind the scenes by owner Paul Caddick and chief executive Gary Hetherington.

“I remember Gary Hetherington coming into Leeds’ team room at the start of 1998 and said his vision was for Leeds to be world champions, and I remember players looking around and raising eyebrows,” Harris said.

“You could see it grow from there and there was a feel with Graham coming in he was expecting silverware, and there was a massive mentality shift at the club and probably what Leeds is today.

“To win that first silverware in 1999 was pretty special because it was 21 years since they’d won the Cup. You just felt the pressure removed from the club.”

As had been the case for Harris when Brian Johnson resigned at Warrington, the departure of Murray from Leeds to return to his homeland in 2000 led to him considering where his future lay.

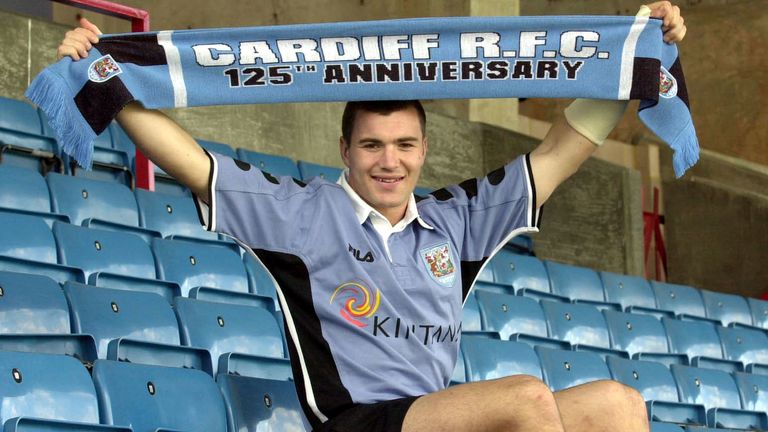

It turned out to be in the 15-man code, finally acquiescing to overtures from the Welsh Rugby Union which had been made since the sport legalised professionalism and joining Cardiff in a high-profile £1.5m transfer in 2001.

The switch was partly motivated by a desire to play in front of big crowds at international level after witnessing 78,000 fans inside the Millennium Stadium for Wales’ Test against Japan just days after playing in front of just over 1,000 at Llanelli’s Stradey Park against Lebanon in the 2000 Rugby League World Cup.

He was doing that just three games into his union career when chosen in the team to face Argentina, although he admits now he felt a huge amount of pressure due to the intense media coverage and the expectations of the passionate Welsh fans.

I felt a huge amount of pressure on my at the time and it took me about six months to get used to it.

Iestyn Harris on his switch to rugby union

“I was at a petrol station filling my car up and there was an old lady next to me doing the same,” Harris said. “I just smiled to say ‘hello’, she did a double-take, turned around and said: ‘You’d better be worth the money’.

“About three days later I was playing my first game for Wales and I was in the line-up and I’ve got my arm around Craig Quinnell who is 6ft 8in, and all I could think of was this woman at the petrol station.

“That in itself, that smallest thing – I felt a huge amount of pressure at the time and it took me about six months to get used to it.”

A chance meeting with Bradford head coach Brian Noble when the Bulls lifted the 2003 Challenge Cup in Cardiff paved the way for him to return to league, rejecting the opportunity to go back to Leeds where Danny McGuire, Kevin Sinfield and Rob Burrow were beginning to make their mark in the halves.

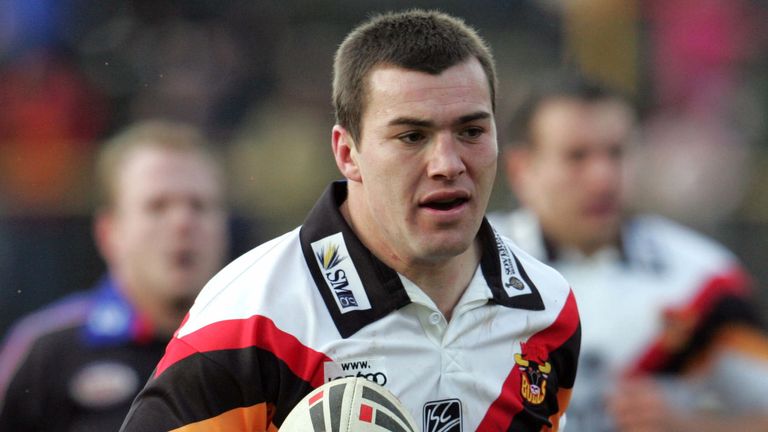

Harris had plenty of talent to work with at Odsal though, forming a half-back partnership with Paul Deacon and having the devastating presence of Shontayne Hape and Lesley Vainikolo on the left edge as the team secure Super League and World Club Challenge glory in 2005 and 2006 respectively.

“It was a different chemistry with me and Bradford,” Harris said. “It was very much a big shift to the left edge because that was our strength.

“If you’ve got that strike, you want to go to that quickly and the amount of times you got a message from the coach which was to give Lesley the ball or give Shontayne the ball.

“A lot of my role was setting things up to give them space along with Paul Deacon, and probably the half-backs were not the dominant fixtures.

“The Bulls were probably at the height of their powers… it was great to be involved in and it’s sad we don’t have that in our game now.”

Source: Read Full Article