Darker times lie ahead after year cricket would like to forget

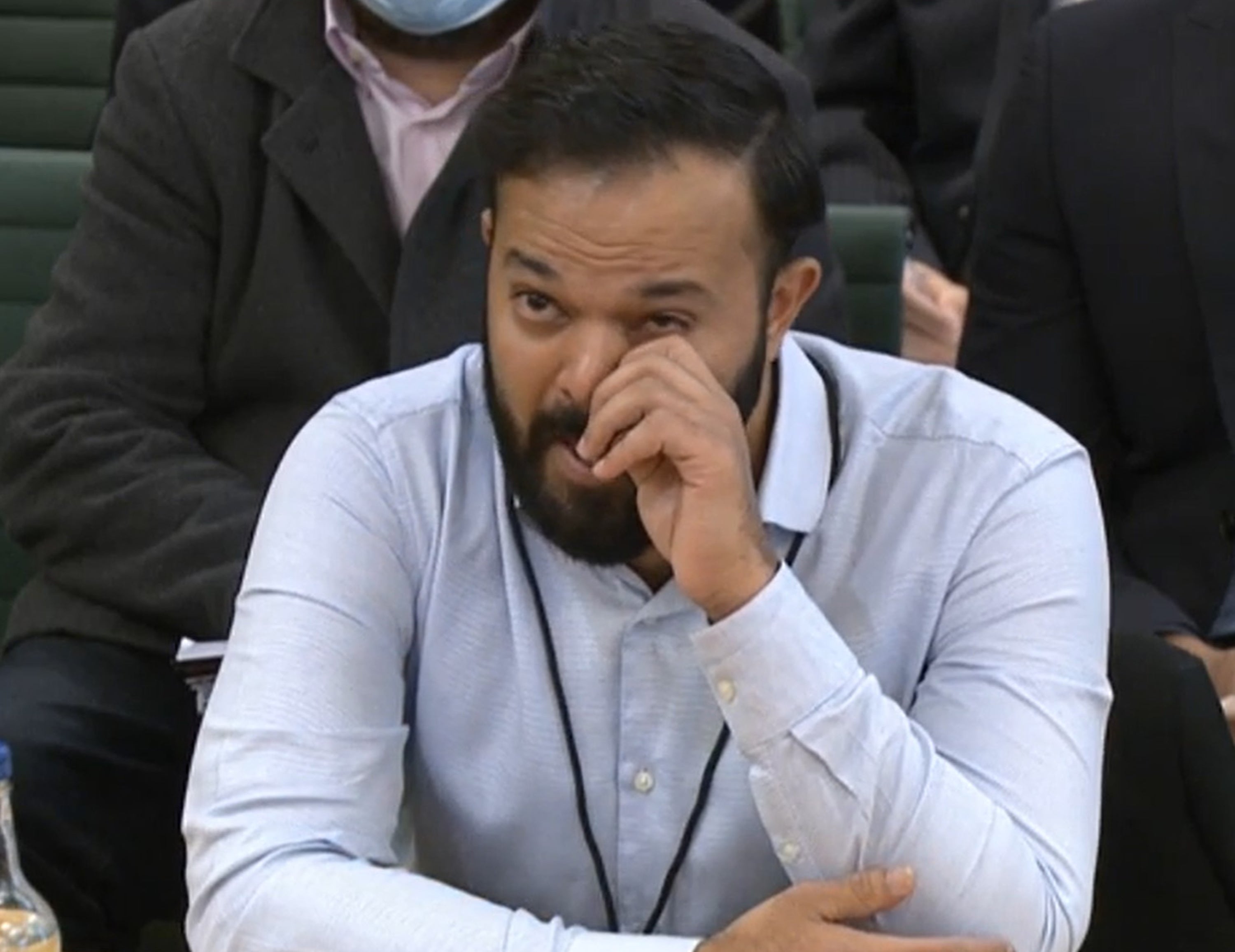

Azeem Rafiq’s testimony was a dark moment for cricket

Starting an annual review with the events of 16 November feels like opening a book somewhere near the end. But this was the day English cricket had more eyes and ears tuned to its frequency in 2021. A seminal moment in a challenging year for the summer game.

It was on this date Azeem Rafiq sat in front of the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport committee and re-opened his scars, more than a year after going public with stories of abuse and institutional racism. The journey to this point had been tough, riddled with the usual snakepits whistleblowers must navigate to tell their truths. In many ways, it was a triumph he had made it to that chair at all.

He relayed stories of a toxic dressing room during his time at Yorkshire County Cricket Club, replete with gut-wrenching tales including having wine poured down his throat as a 15-year-old. He spoke of high-profile pundits briefing against him behind his back – even to his face – and a distinct lack of support from the Professional Cricketer’s Association and the England and Wales Cricket Board themselves. And with the benefit of parliamentary privilege, he named names.

Current Yorkshire and England cricketer Gary Ballance was one, so too revered former captain Michael Vaughan and commentator David Lloyd. All released statements protesting their innocence, deflecting as they could but wearing sizeable blows.

Meanwhile Yorkshire, who had deflected the most, began to accept their fate. Roger Hutton stepped down as chair, as did CEO Mark Arthur as sponsors cut ties in their droves. Lord Kamlesh Patel was instilled as the new director and chairman and proceeded to cull 16 members of staff, including director of cricket Martyn Moxon and head coach Andrew Gale.

Recommended

Rafiq’s harrowing testimony had huge consequences for many

It was there more tangibly in the stories following Rafiq’s testimony throughout the county system. Even right to the top with the England dressing room coming under scrutiny for alleged use of the word “Kevin” to describe people of colour. The first day of the Test summer was marred by the emergence of historic tweets from debutant Ollie Robinson resulting in the bowler missing the next Test against New Zealand as an investigation played out behind the scenes and in public. Captain Joe Root was also part of the collateral in this reckoning for the men’s game.

As it happens, Root stands as a reminder cricket was actually played in 2021. His 12 months with the bat have been the greatest of an already decorated career: 1,708 Test runs strummed with a chorus of six centuries taking him third on the list of calendar year hauls. Unfortunately, acknowledgement of that achievement also brings into focus an utterly miserable time in whites.

Nine defeats across 14 Tests marred the worst year in the format for England, which might have been 10 in 15 had India not hot-footed it out of the United Kingdom as Covid-19 threatened to spread throughout their group. A series win against Sri Lanka in January promised much, as did a convincing opening win in the first match of the series away to India. Alas, they were ransacked in the four remaining games, losing that series, the home opener against New Zealand, before being 2-1 down for India’s return leg. Come the end of December, they had lost the first three Tests in Australia inside 12 days to give up the Ashes in the meekest way imaginable.

Of course, there were plans. There are always plans. Rest-and-rotation saw players shuffled in and out at pre-planned intervals across the three-month stint in Asia – far too long at the best of times, never mind a global pandemic. Well-intentioned given the schedule ahead but, ultimately, for nothing.

Having dominated the early stages of the T20 World Cup, England were stung at the death of their semi-final as New Zealand exacted a modicum of revenge for 2019’s 50 over World Cup Final. That the Blackcaps went on to lose to Australia in the final made it that little bit worse from English perspectives, not least because they had trounced Australia by eight wickets in the group stages.

By then, national selector Ed Smith – the brainchild of the R&R – had been ousted, replaced in totality by Chris Silverwood as the head coach was given the keys to house to go with the car by director of men’s cricket Ashley Giles. Both will do well to survive the fallout of the shambolic Ashes.

England’s men have slipped to an embarrassing Ashes defeat

Meanwhile the domestic game emerged from 2020 like a prisoner emerging from incarceration, blinded and deafened by a once familiar world that had changed immeasurably. The Hundred was the source of that assault on the senses, its maiden campaign getting underway a year later than planned.

It both inspired those previously uninterested or who had erred that way while offending the diehards who were put out of joint and sync by influencers and the best and brightest of the county game stolen away for something blue, if only for a mid-summer window.

Analysing The Hundred in its first year is hard given any worthwhile critique requires time. But the men’s code, for all its entertainment, carried a nagging sense that all the money, kudos and platforming across broadcasters free-to-air and subscription could have been done just as effectively with Twenty20. Nevertheless, Southern Brave took the spoils.

By contrast, the women’s Hundred was the realisation of something much greater. The groundswell of enthusiasm that had died down following the 2017 World Cup win was shocked back into existence as young girls (and boys) of different backgrounds found inspiration from previously hidden figures.

The key difference with the men’s competition was availability: home and abroad internationals shared the pitch with county stalwarts and young up-and-comers. Alice Capsey of the Oval Invincibles (the eventual winners) showed both the exuberance and fortitude was both a testament and belied what it is to be 16 going on 17. Scotland international Abtaha Maqsood spun away in her Birmingham Phoenix orange hijab and became an overnight inspiration.

It dovetailed neatly with a fuller programme for England Women, who recorded home and away series wins over New Zealand and at home to India in one-day and T20 competition. They also ticked off Test match number 96 against India, which but for the Bristol rain could have been a classic. It provided another stepping stone for Sophia Dunkley, who became the first black woman to represent England in Tests, marking the occasion with a crisp 74 not out.

Ahead of the Ashes and 50-over World Cup at the start of next year, 2021 provided yet more evidence the women’s game is more than capable of thriving on its own. The number of English-based professionals is now up to 61. The talent pool is only getting deeper.

Recommended

It is bleaker for the men, not least at the very top. Beyond the poor Test results, there is a real sense we have reached a critical point on welfare, performance and administration.

Ben Stokes’ broken hand during the IPL, the rush to get him back to captain a Covid-replacement squad during ODIs against Pakistan and the greater rush to take him to Australia speak of an unworkable schedule and a penchant for temporary fixes. More alarming was his enforced break that took him out of action from July until the end of the summer for the sake of his mental wellbeing. Here was the great English action hero pleading for relief.

Speaking of over-reliance, we seem to have reached the end days of the Anderson-Broad duopoly. Both missed the Test in Brisbane, with Stuart Broad subsequently sitting out the series losing innings and 14-run shellacking at the MCG. And amid the sadness of the split is a nagging feeling there last few years – particularly this one – has been something of a waste.

Addressing the long-form side is overdue and will be harder than ever given the state of the County Championship and its incumbents. The counties themselves have less power and their red ball players disillusioned. Recalibration will be painful, and may even chip away at the exemplary white ball standards that could make amends for their World Cup failure with another global T20 event at the end of 2022 in Australia.

What is certain is the ills exposed on both sides of the boundary throughout 2021 will not simply vanish once the clock strikes midnight on 31 December. English cricket is fractured, in need of a little more soul searching and a lot of love in 2022. The darkest hour may be before the dawn, but darker times are still to come.

Registration is a free and easy way to support our truly independent journalism

By registering, you will also enjoy limited access to Premium articles, exclusive newsletters, commenting, and virtual events with our leading journalists

{{#verifyErrors}} {{message}} {{/verifyErrors}} {{^verifyErrors}} {{message}} {{/verifyErrors}}

Already have an account? sign in

By clicking ‘Register’ you confirm that your data has been entered correctly and you have read and agree to our Terms of use, Cookie policy and Privacy notice.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy policy and Terms of service apply.

Source: Read Full Article